It has been a great year in 2016. I’ve been able to write more about the motivations for learning languages—and have successfully stirred up some controversy. My goal has been to highlight privilege among language learners and to shine light on those who speak less-commonly studied languages. For example, here is my most controversial post from 2016: “Language hacking ≠ language love”.

One problem has been that I didn’t spend as much time learning languages as I would have liked. So for 2016, my goal is to spend more time on Oromo and Somali. I may work on a little Serbian, since I used to know some and we have a Serbian exchange student living with us currently. Tagalog may find its way in there, too, as an associate from Manila recently joined my team at work.

In this time of growing intolerance and shrinking globe, learning languages has never been more important or political. While I have been writing discoveries made by learning languages and focusing on the languages of my community, I want to turn back to those languages for a while. Time to get back in the trenches.

I will also work on some other writing projects that have been requiring more attention.

So, I will take the next month off. I will come back in February with a summary of progress up to this point.

See you in a few weeks!

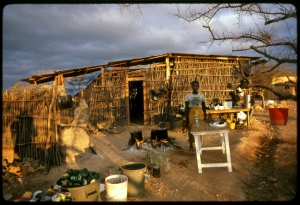

Photo by UW Digital Collections – UW Digital Images, No restrictions, Link